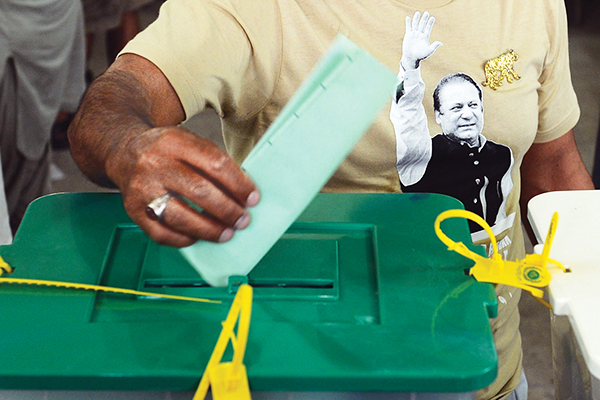

Arif Ali—AFP

Pakistani voters proved many predictions wrong.

Forget all the bogus insta-analysis offered by rushed hacks repeatedly proven wrong, here are some irrefutable conclusions from Pakistan’s elections:

The Spill Factor

Scenes of a bloodied, semiconscious Imran Khan being carried to care had Pakistan gasping. But this wasn’t Liaqat Bagh, where Benazir Bhutto was assassinated on Dec. 27, 2007. The national hero had fallen, on May 7, from a forklift hoisting him to a high stage at an election rally in Lahore. Typically, Khan failed to capitalize on the outpouring of sympathy. When he spoke from his hospital bed that night, clearly in pain, he demanded Pakistanis vote for his party or deal with five years of suffering. Some found the footage moving, others thought it was imperious (Khan also refused to meet rival Shahbaz Sharif, who came to call on him at hospital). Soon enough Pakistanis calmed down and got some perspective: Khan was the victim of his own party’s mismanagement—not, of course, terrorism. If Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf’s know-it-all campaign manager Asad Umar couldn’t organize Khan’s safe ascent to a stage, was the party really ready to run Pakistan? Voters said no.

Khan’s Hung Parliament

The realization came late to the Pakistan Peoples Party. On May 9, the last day of campaigning, the PPP ran attack ads on TV specifically targeting Khan and his PTI. (The Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) also did the same.) Many, including the high priests of PPP strategy, had believed Khan would tear away conservative voters from the PMLN, putting the PPP in best place to take advantage of a hung Parliament and sneak back into power in Islamabad. The vote proved right the PPP’s belated realization that the PTI would dent its constituency in the country’s largest province, not the PMLN’s. Some in the former ruling party had also expected the Army to boost the PTI’s fortunes on May 11. That didn’t happen either. In fact, PTI’s Shireen Mazari has since claimed that (the Army’s) “agencies” had “abducted” and “beat up” her party’s polling agents to ensure an unqualified win for the PMLN.

Peer (Networks) Pressure

These were the Facebook and Twitter elections. Before the polls, parties like PTI amassed passionately vocal support on social media, which skewed perceptions of who would win on May 11. While some delicate (and hypocritical) voters put off by the passion of PTI’s supporters may have gone for other parties, for others social media provided a sense of community and commitment. PTI didn’t sweep the elections, but its social media support did translate into electoral wins—many had thought it would not. On Election Day itself voters proudly posted their just-voted pictures urging others to step out and do the same, while videos of alleged rigging and polling irregularities were shared with viral intensity making the vote questionable. Further proof that online peer networks mattered: the Muttahida Qaumi Movement held a presser after the polls decrying its “trial by social media.”

Lame-Stream Media

Taking their cue from anything-goes professions and self-punditry on social media, cable news channels outdid each other in their irresponsible zeal on May 11. In the morning in Karachi, Chief Election Commissioner Fakhruddin G. Ebrahim thanked TV journalists for their pre-elections coverage. By the evening in Islamabad, a spokesman of the Election Commission expressed dismay at channels announcing results in different constituencies when polling had not even officially closed: “We will hold them to account.” Even before polls closed at 6 p.m. across Pakistan (and 8 p.m. in Karachi), channels aired “unofficial, provisional” counts, declaring winners with only fractions of the results in. The disconnect between who actually won and who the channels had declared as having won reified impressions of widespread rigging, threatening to delegitimize the democratic exercise.

Incumbency Albatross

The PPP and the PMLN were reelected to run Sindh and the Punjab, respectively, with greater numbers than they won in the 2008 elections. Incumbency was not a factor for either party in its home province. Pervaiz Elahi, former deputy prime minister, and Naveed Qamar, a former water and power minister, both won their National Assembly seats, as did both of President Asif Ali Zardari’s sisters. It appears that power outages and perceptions of corruption were of no concern to voters in Sindh, and to some voters in the Punjab. The strong showing of the PPP owed in no small part to the Benazir Income Support Program, the national handout scheme which won over Sindh’s rural poor. The Taliban-decimated Awami National Party didn’t retake Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. But this was likely the result—as his stepmother said—of the party chief, Asfandyar Wali Khan, abandoning the province and setting up camp in Islamabad.

Politics of Principle

Nawaz Sharif defied convenient categorization throughout the campaign. The PMLN boss mostly put principle over politics, but he was pragmatic. Many politicians who had betrayed him by joining the Musharraf-led government were awarded party tickets, and many of them won. At the same time, a news report claimed the PMLN had also absorbed alleged terrorists into its fold. (It denies this.) But most parties, including the former federal coalition partners, have their own militant wings, according to the Supreme Court. The PMLN does not. The pigeonholing of Sharif fell apart with the case of Maulana Ahmad Ludhianvi, former chief of the banned Sipah-e-Sahaba. Newspapers claimed the PMLN was working with Sahaba’s Ahle Sunnat wal Jamaat. But, tellingly, Sharif put up a candidate against Ludhianvi, who was kept from his ambition to gain a larger bullhorn against Pakistan’s Shia community by entering Parliament.

The General’s Election

Pervez Musharraf, the former president and Army chief, was disqualified by the courts from running for the National Assembly from any of the four cities he had hoped to. To protest against his house arrest in Islamabad, Musharraf’s All Pakistan Muslim League announced it was boycotting the elections. But by then the ballot papers had already been printed. The APML surprised pundits by winning one National Assembly seat and one seat in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa legislature, both from Chitral. Musharraf ended self-exile and came to Pakistan on March 24, knowing full well the threats against him, to prove he’s not just a Facebook phenomenon (he has almost a million fans on the social media website). APML’s Iftikhar Uddin, a covering candidate for Musharraf, won his National Assembly seat defeating his nearest rival from the PTI by 5,590 votes.

By dismissing PTI voters as the ‘elite’ is to speciously claim that their voice somehow matters less.

Class Warfare

Since the vote, the PTI, MQM, and, disappointingly, the PMLN have been fueling class warfare at a time when consensus and national unity are required. The PTI protesters—charging both MQM and PMLN with polling irregularities—are not out-of-touch One Percenters. Claims by PMLN’s Saad Rafique, the target of PTI’s ire for his win in Lahore, that the rich broke for PTI are false and irresponsible. The PMLN, which has supplanted somewhat the PPP as the “party of the poor,” had demonstrable support from the business community, “posh area” dwellers, and liberals. Voters across the economic spectrum queued up, some for hours, to make their voices heard on May 11. By dismissing PTI voters, who were good Samaritans on polling day, as the “elite” is to speciously claim that their voice somehow matters less.

Moving On

Taliban threats did suppress voter turnout, especially in Balochistan. (According to the EU Election Observation Mission, 64 people died and 225 were injured on May 11.) But percentages aside, more Pakistanis voted in the 2013 elections than in any other. The Election Commission’s polls management under Ebrahim was less than stellar. In many constituencies, polling staff did not show up on time or did not have the complete voter lists or voting materials. The ballot design resulted in a small fraction of the vote being voided—these figures were posted on the Commission’s website but have been removed. The Commission’s 8300 cellphone service sent out wrong polling station addresses to some voters and crashed on the day of the elections, keeping some from voting altogether. “Some mismanagement” and “shortcomings,” says the EU’s preliminary report, “somewhat marred the process.” And the Free and Fair Election Network says the elections were only “relatively fair.” The PTI and PPP have also criticized the Election Commission. But most Pakistanis just want to move on.

From our May 31, 2013, issue.

2 comments

This piece is extremely cynical about PTI and all too willing to close eyes to all the rigging that took place and brought PMLN to the front in Punjab elections. They won more votes than in 2008? And when 100s and 1000s protest in different parts of Punjab that rigging was done through CNICs bought off people for meagre PKR500 or promises of bikes in lieu of so and so number of votes… that’s not mentioned at all.

We as a nation need to move on rather than protesting on the streets. If you people have some problem with the elections then u need to go and register your complains with “Evidence” to the right forum I.e Election Commission rather than disrupting lives of people. Accept your mandate and now do something rather than complaining. PTI lost the elections because they were crying before and after the election. No please move on and do justice with your mandate.