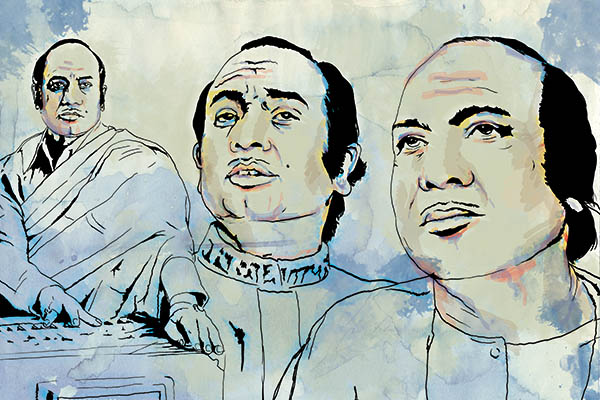

Illustration by Minhaj Ahmed Rafi

The life and times of Mehdi Hassan: singer, composer, and legend

As the voice of Pakistan’s aching, lovelorn heart since he began his career in 1957, Mehdi Hassan was used to being stopped by fans—at airports, in the marketplace, at weddings. Years ago, he was stopped on the road—by gunmen. Luckily for Hassan, the armed robbers quickly recognized that the man they were about to mug was that man, their favorite singer. But they were not about to let him off just like that. They asked that he sing a couple of lines for them. So on a darkened, lightly trafficked Karachi roadside, accompanied by the swoosh of the odd, oblivious vehicle passing by, Hassan serenaded his would-be muggers with verses he delivered in his trademark equanimity.

The next highway robbery Hassan suffered was an unhappier one: he was deprived of his car, and left stranded on the Karachi-Hyderabad superhighway. What’s worse, Hassan’s notebook, page after page of which was filled with ghazals and songs from known and hardly-known poets, was on the backseat of the car. It was never found again. “The car was insured, but the notebook wasn’t,” he told me.

For his admirers across the Urdu-speaking world, there was great relief that the rumor last month of his death remained just that, a rumor. Hassan has been wheeled into hospital far too many times over the last 12 years and he has come perilously close to having his final hour. A lifetime of smoking has ruined his lungs. He suffers from diabetes, hypertension, a heart weakened by multiple strokes. His immunity is extremely low. But Mehdi Hassan is not one to lay down his arms. And at a frail 84, he continues fighting for his life.

“All this has happened to me in my twilight years,” he told me in May 2001, referring to his failing health. He had had a stroke, his first, nine months earlier in Calicut, India, where he had gone to perform. Hindi, let alone Urdu, is an alien tongue to Malayalam-speaking Calicut. Yet, he sang to packed music halls there. When I met him, the right side of his body was paralyzed, but speech and physiotherapy had helped. So he spoke with some difficulty but answered all questions sportingly. An Indian friend of mine who had wanted to meet Hassan tagged along with me. When I introduced her, somewhat apologetically considering the state of his health, he graciously allayed my concerns. “The Indians have as much right over my ghazals as the Pakistanis,” he said. “They have showered me with no less degree of love.” I wrote up this exchange for a newspaper report which India’s then prime minister Atal Behari Vajpayee happened to see. He responded by writing a letter inviting Hassan to India.

Four years later, Hassan traveled to India for ayurvedic cures. He met Vajpayee on that trip as well as Bollywood royalty from Dilip Kumar to Amitabh Bachan to Lata Mangeshkar and the late composer Naushad. Indeed, as he rightly acknowledged, Hassan has always been showered with love by fans in India. Oscar-winning Indian composer A. R. Rahman cites Hassan as an influence. Ghazal singer Jagjit Singh, who died last year, had said that no ghazal singer could ignore Hassan’s artistic example and mastery of the genre. India, Nepal, and Pakistan have all bestowed state honors on Hassan, an unassuming former car and tractor mechanic born into a family of singers in a village in Rajasthan, India.

Hassan is called Shahenshah-e-Ghazal, but this soubriquet glosses over his contributions to semi-classical, folk, and Sufi music. He recorded tracks for Lollywood films in the ’70s, lending creative weight and emotional texture to the works. Hassan is celebrated for the endless forms he gave ghazals through experimentation and crosspollination of styles and influences in his quest for perfection, but, folk singer Abida Parveen maintains, people tend to overlook his complete command over laykari, the cross-rhythmic play. (Once, in the 60s, his perfectionism had him arrive at the Karachi Press Club hours ahead of a scheduled performance. Hassan had heard that radio personality Raza Ali Abidi lunched at the club and wanted to catch him to be doubly sure about the pronunciation of a few words.)

In his later years, Hassan was saddled with a sort of stage son. Arif Mehdi, one of the singer’s 14 children from two wives, both deceased, is the one who calls the shots in the family and signs Hassan up for performances that the helpless, wheelchair-bound father is clearly too weak and unwell to undertake. Arif is also responsible for the singer’s fortune, or lack thereof.

“What happened to all the money that your father earned during his long and prosperous career?” I once asked him. “Ours is a large family, you see, and he was the sole breadwinner,” he said. I wasn’t convinced. The fact is that Hassan is living in virtual penury, unable to pay his expensive medical bills, dependent on the kindness of strangers. Fortunately, the Aga Khan University Hospital has never refused Hassan care over unpaid dues and his neurologist Prof. Aziz Sonawalla has never charged him.

Of course, Hassan was never one for vulgar matters like money. What most mattered to him was the verse, regardless of the reputation or recognition of the poet. He sang Ghalib and Faiz and owned them anew. By singing their words, Hassan launched the careers of poets like Razi Tirmizi and Saleem Gilani. Many of the ghazals Hassan performed were composed by him and often inspired by or based on ragas known and unknown. But no matter whose words he sang or what forces shaped his music, the result was always the same: the man sitting cross-legged on the floor with the organ he could play by ear sang a deeper truth that hit all the right notes with audiences across the decades.

Two years ago, while reviewing a book on an Indian musician, it struck me that there were no tomes on Pakistani artists like Mehdi Hassan. I decided to correct this grievous oversight. By this time Hassan had lost his voice. But there were many—in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh—who were familiar with the man and his legendary talent. Things quickly fell into place. My biography of Hassan was packed with rare photographs and was released with a double album accompaniment which included forgotten recordings.

As soon as I got my copy of the book, I rushed to see Hassan. “Ah,” he said, almost sotto voce. His daughter-in-law held the book before him and turned the pages. His face lit up. As I was leaving, Hassan mustered the strength to say a single word to me: “Shukriya.” The book, I was told, remained on his bedside table for days.

Noorani is the editor of Mehdi Hassan: The Man and his Music

From our Feb. 10, 2012 issue