Matthew Lee High

In focusing on military courts, the government is trying to take the easy way out in the fight against terror.

The Government of Pakistan wants to revive military courts to fight terrorism. Military courts were established on Jan. 6, 2015 and granted permission to try civilians charged with terrorism in the wake of a terrorist attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar on Dec. 16, 2014. The constitutional amendment was accepted by opposition parties as also by a majority decision of the Supreme Court of Pakistan because of a two-year sunset clause—i.e., this special arrangement will be undone after two years. On Jan. 7 this year, the courts were packed up.

Now, following a spate of terror attacks, the government wants to revive them. Will the measure reduce terrorist attacks? The short answer is no. Here’s the long answer.

First, let us begin by accepting the rationale for the courts. This is how the argument went two years ago: the criminal justice system allows terrorists to slip through and they go back and mount more terror attacks. Until the normal judicial process can be strengthened, we need special courts. Extraordinary times demand extraordinary measures. This is that exception.

Correct. Exception creates a legal fiction but it’s been around. The Romans called it iustitium (literally, standstill or suspension of law). Just war theorists talk about ‘emergency ethics’, resorting to war-fighting strategies that could and cannot be ordinarily condoned. But it should be evident that exception denotes exactly that—exception. It cannot be the norm. There’s yet another fact: measures taken in an emergency remain contentious even within that framework. Outside of that framework they would generally be considered illegal, unconstitutional, violative of rights and due process and downright criminal.

Put another way, the National Action Plan under which the special courts were created (see point 2 of NAP) also spoke about reforming the criminal justice system (see point 20 of NAP). Even if one were to accept the creation of military courts as an exception, a fact highlighted by the two-year sunset clause, the acceptance was contingent on reformation of the criminal justice system. It is a matter of record that in the two years that the military courts remained functional, the movement on reforming the normal judicial process(es) can be described as zip, zilch and zero.

Nothing surprising about this. There is sizeable literature on how and why governments and organizations tend to ‘satisfice’ rather than ‘optimize’, essentially going for the easy way out and shirking the hard work.

Please note that so far we have argued the issue by accepting the rationale for the courts. Two points have emerged: exceptions can be created but they remain exceptions and cannot become the norm; they are created to respond to a particular situation and to get back to the norm, the ordinary. A third affiliated point is that the government pegged their creation on a promise to reform the criminal justice system but never even embarked on that process.

Let’s now come to some other facts. The entire argument is an eyewash. Terrorism is not a phenomenon military courts can fight and reduce or eliminate even if they were to sentence to death every accused brought before them and those sentences were also carried out—unless, someone could prove an absolute causality between the number of terrorists we kill and the corresponding reduction in terror attacks.

Granted, operations that net and kill terrorists do set the groups back a little; busting sleeper and other active cells can preempt and disrupt plans. But all of this is temporary. The threat is protean and morphs. This means two things: fighting terrorism is a continuous process until we can find and address what causes it and neutralize that; two, no single measure can strike at what sustains terrorism in isolation. The second point is important because policies and plans have to work in tandem and support and complement each other if the overall strategy has to be effective. The government has singularly failed at that.

It’s easy to sell bullshit because, to mix metaphors, in testing times people will even clutch at straws. This is precisely why we see a revival of this argument about the military courts. Will the courts manage to convict more? Yes. Does higher conviction mean their process is more effective than that of normal courts? No. In fact, higher conviction rates are precisely because these are secret trials and the law is applied in ways that will not pass even the basic test of due process.

Okay, we have to deal with terrorists and let’s not go all faint-hearted about niceties of law. Sure. In which case, here’s the hard-hearted test: damn these terrorists and put them to death with or without any process. Will that reduce terrorism? Empirical evidence suggests it won’t. We have done it both ways and that hasn’t worked. The Phenomenon, which subsumes within it many phenomena, requires a grand strategy that addresses endogenous and exogenous factors and the latter are usually outside the direct control of a state/government.

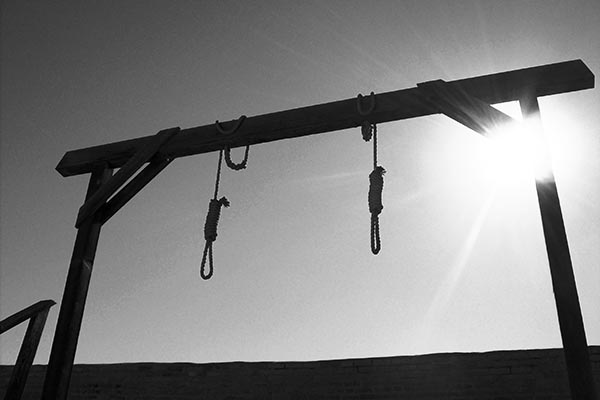

Meanwhile, statistically, to quote from the International Commission of Jurist’s Military Injustice in Pakistan: Q&A: “The military has acknowledged the convictions of at least 144 people by military courts for their ‘involvement’ in terrorism-related offences since January 2015. Out of the 144 people convicted, 140 people have been sentenced to death. Twelve out of the 140 people sentenced to death have been hanged.”

Only 12 have been hanged. Compare this figure with the total number of hangings since the moratorium was lifted in Jan 2015 and one realizes that we have been happily hanging people by the neck for crimes other than terrorism! Also, if only 12 condemned were actually hanged, it belies the argument now being trotted out that the current wave of terrorism is because the military courts packed up. There was a reprieve not because the military courts were sentencing terrorists but because there was a concerted, multi-pronged operation that reduced the capacity of terror groups and forced them to hunker down until they could get fresh recruits, reorganize, re-mobilize and get back in the fight.

Finally, to the draft the government has come up with. The opposition parties, including the PPP and the PTI are objecting to the draft. The government had initially moved to amend Article 175(3) of the Constitution, which had allowed the military courts to hold trial of persons “belonging to any terrorist group or organization using the name of religion or a sect.” To appease its ally, JUIF of Maulana Fazlur Rehman, the government has removed the words “using the name of religion or sect.” The opposition fears that the law could be used against them for “arm-twisting or political victimization.”

Leaving aside other arguments against or in favor of the military courts, the question that needs to be asked of the government is, what does it intend to do with the military courts if not to try those who use ‘the name of religion or sect’? The terrorist groups we are fighting have grounded their political violence in religion and sect. This is precisely why Fazlur Rehman is objecting to the draft—his party’s elements are linked to the sectarian outlook that has created the mayhem. If the government removes the qualifying phrase, it has no case for the military courts to begin with. The eyewash at this point becomes hogwash.

Two, the opposition is not mounting any sophisticated argument against the military courts per se. They are more concerned about whether this law, if in play, could be used against them for political purposes. That should give us an idea about the state of debates in our legislative chambers and policy interests on both sides of the aisle.

Haider is editor of national-security affairs at Capital TV. He was a Ford Scholar at the Program in Arms Control, Disarmament and International Security at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C. He tweets @ejazhaider