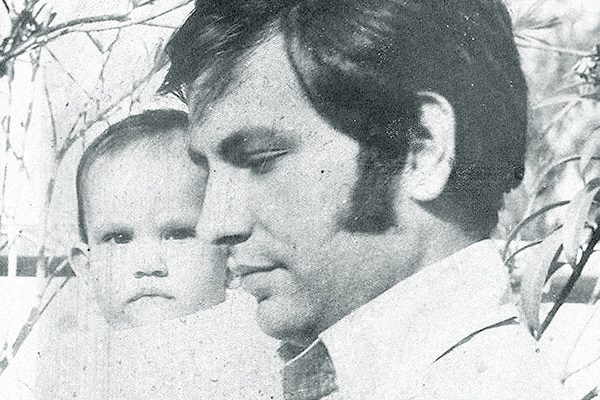

Courtesy of the Taseer family

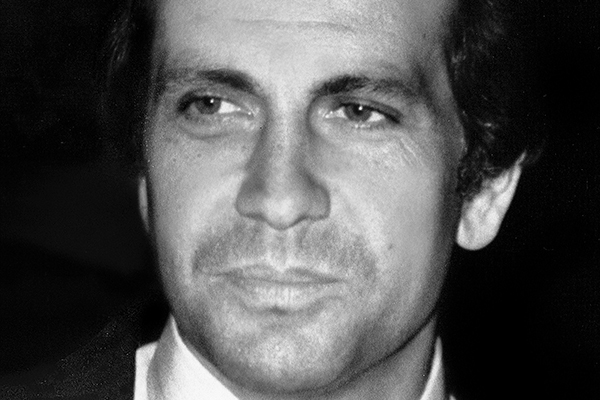

Known to millions as a politician‚ media mogul, and an outspoken critic of Muslim radicals‚ Salmaan Taseer, Pakistan’s bravest man, was even more impressive to those of us who knew him in person.

Pakistan is not the bravest nation in the world.

It is a terminally sick country where‚ to borrow from Yeats, the best lack all conviction and the worst are full of passionate intensity. Salmaan Taseer did not lack conviction. In fact, the governor of the Punjab was assassinated in Islamabad on Jan. 4, 2011, because of that.

Taseer, 66, was known to millions, and he was the same man in public that he was in private: quick and occasionally provocative—traits that were refreshing to many, but could have seemed arrogant to the uninitiated. I knew Taseer as a politician, family friend, and employer. And the truth is that I had always wanted to be like him: brave, clear minded, clever. A few years ago, I went up to him excited about a new discovery.

“We share the same birthday, May 31,” I said.

“Not the same year, I hope,” he dryly replied.

On Nov. 20, 2010, Taseer visited the jailed Aasia Noreen, a Christian woman sentenced to death for allegedly blaspheming against Prophet Muhammad. Taseer wanted a presidential pardon for Noreen, and rationalization of the blasphemy laws. But the religious right would have none of it. They declared him a heretic, an apostate, and loosed their fury on him in fulminous displays of typically misplaced self-righteous indignation.

Under pressure, the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party, Taseer’s party, distanced itself from the governor—and from Sherry Rehman, another brave life of the party who had also urged a review of the controversial laws. Like Taseer, she has a fatwa on her head and tens of thousands of foaming mullahs protested in Karachi against her on Sunday. The interior ministry has advised her to leave the country, but Rehman is staying put. “Nobody is driving me from my country,” she told Newsweek Pakistan on Saturday.

On Dec. 31, fanatics across Pakistan had burned Taseer in effigy and demanded his head. Taseer posted on Twitter the next day that he was “unimpressed” by the mullahs’ protests, which were “abusive” and “well organized” but had “no general support.”

The mullahs found specific support in Mumtaz Qadri, a deeply troubled member of the Elite Force. Days before Taseer’s assassination, Qadri attended an anti-Taseer protest in his hometown of Rawalpindi. It was there that he decided to do something about the governor. The 26-year-old policeman, already viewed with suspicion within the force for the ferocity of his “religious” views, asked to be assigned with Taseer.

On Jan. 4, 2011, at around 4:15 p.m., as Taseer turned toward his Islamabad house after lunch at a nearby café in Kohsar Market, Qadri opened fire. He had reportedly asked others in the security detail to take him alive. Closed-circuit camera footage shows at least three other security personnel simply standing by as Qadri fired at Taseer, reloaded his weapon, and fired again. Unrepentant, Qadri later told TV crews he had murdered Taseer because of the governor’s opposition to the blasphemy laws. Qadri is now in police custody with at least 10 others.

The postmortem report shows that Taseer—who wore the Prophet Muhammad’s name and Quranic verses in a chain around his neck—was shot 40 times. The doctors pulled 27 bullets from his body. Every one of his vital organs was punctured, except his heart and larynx.

The shock of Taseer’s assassination was felt around the world. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said she “admired [his] work to promote tolerance and the education of Pakistan’s future generations. His death is a great loss.” U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon said the governor was “a prominent leader whose death is a loss for Pakistan.” Pakistan declared three days of mourning. And the country went into lockdown immediately after his death was confirmed.

After his murder, spontaneous protests erupted in several cities by nightfall. Taseer’s supporters burned tires and yelled slogans against the opposition Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz), which rules the Punjab and was responsible for Taseer’s security. In the days that followed the murder, supporters held candlelight vigils in Islamabad, Lahore and Karachi demanding justice. The militants have issued a warning against any further demonstrations of support.

Courtesy of the Taseer family

Across the country, reactions to Taseer’s death have been chilling. Within hours of the worst political assassination since Benazir Bhutto’s in neighboring Rawalpindi in December 2007, students from the rightwing Jamaat-e-Islami texted celebratory messages about the murder, and on Facebook, pages lionizing the governor’s killer quickly found hundreds of supporters. Elsewhere in the country, mullahs rallied in support of the killing. Hundreds of lawyers showered Qadri with rose petals when he appeared in court. And he was garlanded by the president of the lawyers’ wing of the PMLN.

Some members of the opposition party spoke dismissively of Taseer and bizarrely downplayed the significance of his murder. There was little remorse among Pakistan’s freewheeling (and conservative) television talk shows for publicizing fatwas against Taseer and misrepresenting his principled position on the blasphemy laws as, itself, blasphemy.

Taseer’s death closes the door on any discussion of the laws. The mullahs and their sympathizers have probably succeeded in scaring reason and rationale into retreat even if a few still dare to speak up, like religious scholar Javaid Ghamidi. “If we don’t speak up now, tomorrow we will not be able to say even the few things that we can today,” he said on Dunya TV. Facing fatwas himself, Ghamidi is in exile abroad.

While Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani has said that his government has “no intention” to amend the blasphemy laws, conservative politicians Imran Khan, a former cricket star, and Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain, a former prime minister, have taken the same position as Taseer: they want amendments to prevent misuse of the law. “Now that the government has decided under pressure that it cannot change the laws, this is a time for a tactical review of the situation, and to regroup for another day,” says the PPP’s Rehman. “The fight against terrorism cannot be fought without a battle against extremism, and we will have to reverse this tide from all sides, not just through military means.”

If Taseer was ever frightened, he never showed his fear; never talked about the threats and bomb scares leveled against him and his family. In a Twitter post on New Year’s Eve, he wrote: “I was under huge pressure sure 2 cow down b4 rightist pressure on blasphemy. Refused. Even if I’m the last man standing.”

Taseer was superhumanly thick-skinned. During the 1980s he endured jail and torture under the Islamist Gen. Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship, which instituted the blasphemy laws. Three years ago, the PMLN pulled pictures from the Taseer children’s Facebook pages and declared that the governor was unfit for public office because he was “un-Islamic.” The move was a public-relations disaster for the PMLN, which had to apologize for invading the privacy of the Taseer family.

An important and often undervalued measure of a man is his children in the values they represent, how they engage with others, and the lives they lead. There is no higher recommendation for Taseer than his six children. To his friends, loved ones and political supporters, Taseer remained accessible and good humored, exuding the confidence of a self-made man, even under pressure.

The son of a Kashmiri poet, Dr. M. D. Taseer, and a British mother, Taseer brought cable television to Pakistan, and, three years ago, sold his telecommunications enterprise to an Omani company for some $200 million. He also developed ambitious real-estate projects as well as two cable TV channels and a liberal, English-language newspaper. It was here that I worked for Taseer, at Daily Times, a paper we launched in April 2002 as “a new voice for a new Pakistan.”

But almost three years after Bhutto was killed, another strident voice against terrorism and intolerance has been silenced. Wednesday afternoon, the day of his funeral, felt unusually cold and foggy for Lahore. Thousands came to pay their last respects despite threats from the militants. Like with the Sufi poet Bulleh Shah, clerics—including the resident imam at Governor House—refused to lead Taseer’s funeral service. As his flag-draped coffin was flown on helicopter from the lawn of the governor’s official residence to an early grave near his private home, “a new Pakistan” never felt so out of reach.

From our Jan. 17‚ 2011‚ issue.