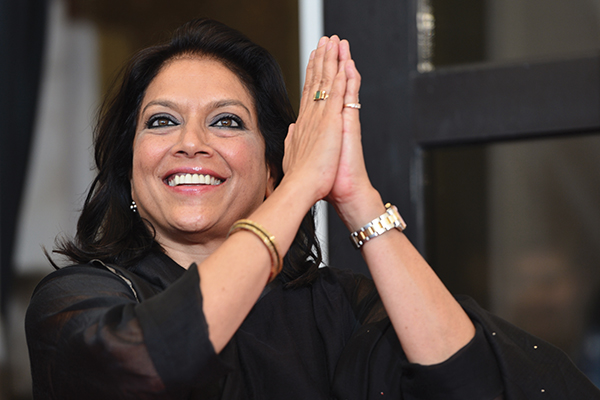

Gabriel Bouys—AFP

In conversation with the Oscar-nominated filmmaker.

We recently spoke with Nair—whose credits include Mississippi Masala, Monsoon Wedding, Vanity Fair, The Namesake, and Amelia—about South Asian cinema, shooting The Reluctant Fundamentalist, and more. Excerpts:

From your Oscar-nominated Salaam Bombay! in 1988 to Danny Boyle’s Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire in 2008, how has Western appetite for East-centric films changed?

South Asia is not as obscure or foreign. It’s a very different landscape now internationally because of the movies that make our part of the world, the subcontinent, more relatable to people. Not to be forgotten is the enormous economic power that South Asia holds. Just that alone invites a whole different level of curiosity. In the Bombay film industry there is a huge influx of foreign film technicians, and the volume and vigor of the industry is so massive that it’s really making it the Mecca for a lot of filmmakers now.

What were some of challenges you faced with The Reluctant Fundamentalist?

It was by far one of the most difficult films I’ve made because of the creative adaption of the novel and then the challenge for raising finances for it. One time this English financier we were lunching with, he had had one too many glasses of wine, offered us a couple of million dollars for the film—which was a big film, shot on four continents, with an A-list cast—and we said that kind of money would not cut it. And he said: “Darling, you can shoot it in Rockaway Beach, but when you have a Muslim at the center of it, $2 million is all you’re worth.” He said what no one had the guts to say. But we managed to make a film with full creative freedom, which in this day and age is a real gift.

How disappointing was it not being able to shoot the film in Pakistan, where the novel is based?

The impediments were really not from within Pakistan, but from international companies insuring the cast and crew. The second hurdle was that we’d have to bring a lot of stuff over. A lot [of equipment] would have had to be brought in and that would have really impacted our budget.

How do you see the future of South Asian cinema?

It’s in a pretty vigorous place at the moment. In India, because the distribution is so varied, you have the ability to make much more experimental stuff happen and be seen. In that sense it’s a very exciting time, so I am heartened by it. I have never underestimated the intelligence of our audience and always made my films my way, with my standards, so they would work in the cinemas of Bombay in the same way they would at Cannes.

What do you look for when you’re picking projects?

I’m attracted to stories with the power of life in them, the inexplicability of life, the strangeness and beauty of it. I love mischief and laughter. Every film and every piece of work really is a political act, and you have to make films with that kind of awareness. My big mantra is that if we don’t tell our own stories, no one else will. There are a hundred people who will tell the story of a mom and pop with a white picket fence and romantic Western escapades, but that’s not for me. I don’t want to sound egotistical but the stories I tell would probably not be known if I didn’t tell them.

What’s next for Mira Nair?

I have a Broadway version of Monsoon Wedding which I’m directing. We are going into workshop at the end of this year and planning to bring it to stage by late 2014 or early 2015. That’s really going to be, I hope, something great. We’ve been working on it for about four years now. Then there’s The Queen of Katwe about a chess prodigy, a very young girl in Kampala, being made by Disney. I’m also in negotiations with a major studio about a fantastic film based in India.

Many of your films deal with issues of identity. Is this a reflection of your own biography?

Since 19, I’ve lived in the United States for a fair amount of time, and when I turned 32 I moved to Uganda, where I’ve lived for 20-odd years. This moving between worlds expands one’s sense of the world. But my identity is pretty rooted in being from India and being very much now a daughter of Africa. I don’t think this has excluded me from feeling at home in New York. I’ve always believed that because my roots are strong I can fly.

From our Aug. 2, 2013, issue.