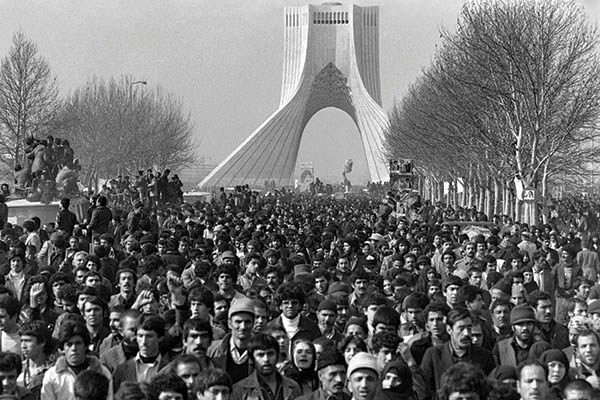

Gabriel Duval—AFP

The history of Iran is that of two nations—the one before the Revolution, and the one that came about after it

Forty years ago this February my life changed forever. Not only my life, but the lives of all my countrymen. The revolution that toppled the last Shah of Iran and replaced him with the religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini changed, for the 20-odd million Iranians then living in Iran, the topography of our hearts.

The Iranian Revolution was a bloody uprising against a despotic Shah who, while giving the West an impression of a progressive modern monarch, stifled dissent at home, crushed political opponents and wielded such terror with his secret police that even casual conversations at bus stops had the power to land one in jail. His treasury full of petro-dollars, the Shah, who had been forced on his people—they preferred the democratically elected prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh—in a CIA-engineered coup in 1953, modernized too quickly and too superficially at home, while abroad he strutted a little too tall, too sure of his own power and potency in a world where the oil man was king. Intellectuals, radicals, traditionalists, socialists, merchants and millions of illiterate and dispossessed gathered under the leadership of Khomeini, an exiled priest whose simple message could be understood by all.

After a year of increasingly violent demonstrations and the imposition of martial law, the Shah and his family left Iran in January 1979 while the austere Khomeini, clad in robes and a turban, his face implacable under its long beard, returned on Feb. 1, 1979. In spite of earlier protestations that he was not interested in political power, in spite of the Communist and Socialist revolutionary groups who had reluctantly accepted him as the leader of the revolution, convinced that he would cede power to them once the monarchy was toppled, Khomeini instantly moved to take power and announced that a referendum would be held to determine the future of the country. The vote, which took place two months later, gave Iranians merely two choices—an Islamic Republic, yes or no. With no options, no debate, no understanding of what an Islamic Republic meant, and with plenty of pressure to ‘vote the right way,’ an incredible 99% supposedly chose an Islamic Republic.

Personal loss

I was nine when Ayatollah Khomeini came back to Iran in February 1979. I was not aware of any of the above, of the tensions and problems bubbling beneath the calm surface of my country. I was a lucky kid from a comfortable middle class family, the sort of new breed of Iranian as much at ease with sitting cross-legged on the floor in my grandmother’s traditional inner courtyard eating rice with my fingers as I was gnawing on massive steaks in Texas. While my parents were modern after the Western model—my mother’s skirts were short and we only donned chadors to go to the mosque for special festivals—my extended family rooted me to my culture and my country. With 11 aunts and uncles on my mother’s side alone, I felt as if we all lived in a big noisy mess of scampering children, and scolding, laughing, loving adults.

Iran for me was not just the snow-capped mountains of Tehran; it was the evenings spent at my uncle’s house telling ghost stories with my cousins and the days when the schools would close because of the severity of the snow. Iran for me was not just the towns and the country and the seaside and the mountains and the rush of city life—it was my favorite aunt’s pink Beetle in which we would belt out the latest Persian pop hits as we drove around, or trips to cafés in Tehran where my youngest aunt would take me after school and order me a coffee mixed with vanilla ice cream while she drank her espresso and pulled on a cigarette as she talked of something called feminism. Until the age of nine, I was brought up as much by my grandmother, my aunts and uncles, as I was by my parents, and this tight-knit, large group of people that surrounded me had as much love for and right to me as my parents did. I can’t remember that I ever felt alone or had any sense of what that even meant before we ran away to England.

And suddenly it all stopped. The picnics and the trips to the seaside and the rough and tumble in the dust courtesy of my male cousins; they all stopped. Things changed and our friends and neighbors disappeared literally overnight, either fleeing to some safe country far away or taken in the night by the local revolutionary committee, their houses abandoned, still filled with all their possessions. The revolution changed everything.

We watched it all play out on our television sets and the rest of the world watched too. The Iranian revolution was the first revolution that the world had beamed into its living rooms and it served to give the world one overwhelming image—of terrifying rage—of my country for decades to come.

In Iran, the executions started almost immediately, when members of the Shah’s regime were executed on the rooftop of a school housing Ayatollah Khomeini. Sharia law was quickly introduced and the very first act of ‘God’s own government,’ as Khomeini liked to call his regime, was to abolish the most enlightened family laws in the Middle East, taking away women’s right to divorce and plunging the marriage age for girls to 7. Hijab laws were soon enforced and women found themselves barred from their jobs if they did not comply and cover their hair. Soon after, in September of 1980, Iraq illegally invaded Iran, embroiling it in a gruesome war that lasted eight years, the last century’s longest war, a horrific combination of modern technology and medieval warfare in which trench warfare and chemical weapons were used for the first time since WWI; a war in which Iran, as the victim, saw its entreaties to the international community dealt with so unsatisfactorily that it remains suspicious of engagement with the West to this day.

Then and now

Forty years on, Iran is a decidedly modern country, arguably the most progressive in the Middle East. Decades of legislation and activism by women has pushed the legal marriage age for girls back up to 18 and the country now enjoys the highest literacy rates of the region (93% with the figure jumping to 97% in the 15-24 age group). Sixty percent of university entrants are women and women hold more than 30% of academic seats at universities and seminaries—the same statistics before the Revolution was only 1%. Women make up 40% of medical specialists in the country and 98% of gynecologists. In addition, a remarkable number of women hold decision-making and political positions as lawmakers, advisers to the president, deputies and advisers to ministers, governors and other decision-making structures and executive management of the country. These statistics alone should alert us to the complexities of the Islamic Republic and how, for many Iranians, the Islamic system has helped with real gains that were not dreamt of under the Shah.

Tehran today surprises visitors. Often called ‘the New York of the Middle East,’ the Iranian capital could certainly give Manhattan a run for its money when it comes to skyscrapers, modern art galleries, glossy shopping malls, independent fashion boutiques and hipster cafés. With nearly 9 million inhabitants—and 15 million in the Greater Tehran area—the vibrant capital of Iran could teach New York a thing or two about population density, with an average of 1.6 people per room in houses across the city. In the leafy northern reaches of Tehran, where wealthier residents make their homes under the peaks of the Alborz mountains, one could easily forget that this is Iran—with its Sharia law and ruling mullahs—as one trendy coffee shop vies with another for the custom of the gorgeous Glamazons and their bearded hipster companions who populate this part of town.

Giant posters of the Islamic Republic’s turbaned-and-robed-founder Ayatollah Khomeini and his successor as Supreme Leader Khamenei adorn the spaghetti of motorways that crisscross Tehran. Vast murals of soldiers who lost their lives in the Iran-Iraq war look down at the young people crowding cafés, shopping in malls, surreptitiously holding hands in Tehran’s verdant parks. It is a disconnect so dramatic—the image projected by the Islamic regime and the reality of life on the ground—that one can be forgiven for sometimes thinking that this is not real life, but the plot of a science fiction novel. With 70% of Iran’s population under the age of 40, most Iranians have known no other reality than life under the Islamic Republic and, connected as they are to the rest of the world through satellite television and the internet, there is little appetite for the sort of political Islam that has reduced their choices, limited their freedom and, most importantly, made a terrific mess of the economy of a country with the third-largest oil reserves and second-largest gas reserves in the world. In a country that claims to be a model Islamic society, about a third of all marriages in Tehran end in divorce. With 23 million people eligible to marry, less than half at 11 million are actually married. Iran now has the lowest mosque attendance of any country in the Muslim world, and the ostentatiously Westernized lifestyles of the offspring of the ruling elite seem to openly mock one of the central tenets of the revolution—cleansing Iranian culture from the ‘Westoxification’ of the Shah’s rule.

In spite of the regime’s efforts to roll back some of these changes—passing a law to positively discriminate in favor of men in university courses, outright banning women from reading certain subjects deemed to be too masculine, and recently banning people from walking their dogs on the streets of Tehran (a response to the very Western trend of keeping dogs as pets)—there is more unrest and dissatisfaction with the Islamic regime than ever before.

Forty is symbol of maturity in the Islamic tradition and Iran is playing up this year’s anniversary in a bid to reignite the spirit of the revolution. However, today’s Islamic Republic faces acute economic challenges as it struggles with a mix of domestic hardships and U.S. sanctions. The national currency, the rial, has sharply devalued against the dollar, driving up prices, while the re-imposition of U.S. sanctions has blocked foreign investment and limited Iran’s oil sales. Last year, the regime cracked down on protests over poor living standards and corruption in over 80 cities and towns. Female protesters have openly challenged the authorities in anti-hijab demonstrations that have been posted online—the Girls of Revolution Street with their quiet civil protest against the hijab are just one example.

Fighting for rights

At the end of 2017, rising prices triggered widespread demonstrations against poverty and corruption in working class areas that tipped over into calls for a change in the system. The unrest posed the most serious challenge to the clerical leadership since the 2009 Green Movement uprising over disputed presidential elections. Some Iranians called for the fall of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who in turn has blamed ‘enemies of the Islamic Republic.’ Small, sporadic protests continue over issues such as unpaid wages. Iranian officials blame the protests on external forces and the situation for dual nationals visiting the country has become precarious, with 14 dual or foreign nationals arrested by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) Intelligence Organization since 2014.

To some, the Islamic Republic looks highly vulnerable. John Bolton, the hawkish U.S. national security adviser, claimed last year that the republic would ‘not last until its 40th birthday.’

He was obviously wrong, but he is not the first to misread Iran. Unlike many other countries in the region, Iran was not created by borders drawn up by Western leaders after WWII. Iranians have been living on the Iranian plateau for more than 3,000 years, making it the longest continuously inhabited area of land by a single nation. It has held its present borders since the 17th-century and is a cohesive nation in which its many different ethnicities are well integrated into an overriding Iranian identity. Iran’s large and educated middle class may be beleaguered by rising inflation and falling standards of living, but while they are a strong force for change, they are too conscious of recent history to court turbulence. And the Islamic Republic, with its unusual mix of autocratic, theocratic and democratic institutions, is actually a very flexible beast, able to adapt itself to social changes in order to hold on to overall power.

For me, the past is, quite literally, another country. The events of 40 years ago in Iran have shaped my life in a way that is impossible to overestimate. Having accepted that we will never go back, I navigate my two cultures now, like every one of the 175 million people living outside the country of their birth—all those exiles, each one carrying silently their own stories, their own losses, struggling with private conflicts that have become increasingly political, particularly for those whose background is Middle Eastern like mine. For all the analysis that you are likely to read about this anniversary, for all the ruminating on the political and social effects of the Iranian revolution, both in Iran and abroad, for all the stories of exuberance turned sour, of political prisoners and human rights abuses, of an extraordinary revolution that then bathed in the blood of its own children, of the rise of an Islamist regime that changed the face of the region and presaged the decline of American influence in the Middle East, what you will not read will be the stories of ordinary people leading ordinary lives who, through no fault of their own, had to find extraordinary courage and strength to leave behind lives they loved to start other lives.

Whether rich and privileged or poor and dispossessed, people do not, for the most part, seek out displacement. When contemplating the Iranian revolution, we would do well to remember that history happens to real people, not just to politicians and kings and people lost in the remote past.

Mohammadi is an author, journalist, broadcaster, editor and public speaker. Her most recent book Bella Figura: How to Live, Love and Eat the Italian Way is launching in Pakistan at LLF 2019