Alena S. Amir

Pakistan’s battles cannot be won without a jealously guarded, independent justice system.

The Pakistani flag rose slowly toward the sky. Our hands were steady as we hoisted it up the pole in the front lawn of the residence of Iftikhar Chaudhry‚ chief justice of the Supreme Court, in Islamabad. About halfway‚ we gave a few sharp tugs on the knot. The flag unfurled instantly‚ dropping a payload of rose petals. It was the morning of March 22‚ 2009. It was the moment of our triumph.

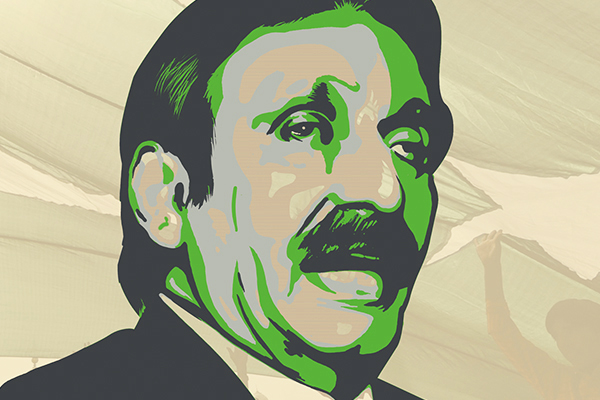

Two years earlier‚ military ruler Pervez Musharraf had ordered this very flag unceremoniously pulled down. This led to what would become the lawyers’ movement: thousands of people‚ led by attorneys‚ taking to the streets around the country to demand Chaudhry’s reinstatement and respect for the rule of law. This mass of people braved bombs and bullets.

On May 12 that year‚ the chief justice’s supporters came under attack in Karachi. The following month‚ a rally was bombed in Islamabad. The Supreme Court restored the chief justice to office that July‚ but Musharraf would have none of it. On Nov. 3‚ 2007‚ the general imposed emergency rule and placed 60 judges under house arrest. Chaudhry was detained‚ along with his wife and children‚ for five months. Last year in March‚ the resurrection of the flag‚ finally‚ symbolized a people’s victory.

Microcosmically‚ the lawyers’ movement represented the ethos of the vast and nationwide popular wave that had been sustained over two long years. The 20 people who hoisted the flag that morning in Islamabad truly represented Pakistan. Not all of them were lawyers‚ but they were each committed to the rule of law. Not all of them were politicians‚ but each was a practitioner of the politics of nonviolence. Not all of them were of one religious persuasion‚ but each respected the beliefs of every other and embraced that plurality. Not all of them were of one political creed‚ but they all believed in the right to disagree and coexist.

They had all come together—each in his or her own way—in a long drawn peoples’ movement against a military ruler‚ his elite coterie of civil and military confederates‚ and the brute force of fundamentalist extremists. They epitomized the only progressive, nonviolent‚ and popular movement for moderate values in the Muslim world. They represented the essential spirit of the body politic of Pakistan: civil‚ peaceful‚ tolerant‚ multicolored‚ multiethnic‚ and wedded to the concepts of the rule of law‚ due process‚ individual freedoms‚ democracy‚ and an independent judiciary. Yes‚ wedded to mere concepts. And striving to realize and actuate them.

The West read these people and their movement wrong. And it kept its distance from both. It remained invested instead in individuals subverting the onward march of the people and the rule of law. It lost an opportunity to win over the populace in an important theater of war. When it chose to stand with individuals such as Musharraf—against popular aspirations—it created grounds for hostility with the very people it needed as allies. It is in this context that the lawyers’ movement must be seen: a popular and nonviolent movement for the rule of law in an Islamic country that is in the eye of the storm. But the language of the law has no listeners amid the thunder of guns and cannon.

The big question now is whether Pakistan can sustain the momentum of the lawyers’ victory and use it against the insurgents. In recent months the restored judges have taken some strong—and controversial—decisions. In July last year‚ the Supreme Court ruled that Musharraf’s regime had become wholly illegal and unconstitutional when he suspended the Constitution‚ imposed an emergency and prescribed a new oath for judges. All subsequent actions of the regime were declared invalid‚ null and void. Judges who had taken oath under the Musharraf dispensation thereafter were removed. Yet despite such iconoclasm‚ the Court validated the elections to Parliament and the induction into office of Musharraf’s successor, President Asif Ali Zardari—even though he had been administered oath of office by a pretender chief justice. In so doing, the Court saved the democratic system in its first major ruling.

Few investors will tread where they fear their contracts will not be enforced.

About 10 months ago‚ the Court overturned an amnesty law‚ Musharraf’s National Reconciliation Ordinance‚ which indemnified criminal conduct‚ including official corruption. This paved the way for several cases to be reopened against many—including the new president. Earlier this year‚ the Court set aside the arbitrary promotions of junior public servants over their seniors. It also invalidated a government contract to import liquefied natural gas through the public sector after finding improprieties in the process. The chief justice has also provided relief to several battered and bartered women being subjected to patriarchal cruelty. On human rights abuses and police brutality‚ the Court brooks no tolerance. It has taken notice of the recent‚ cruel mob murder in Sialkot on Aug. 15 of two young brothers and ordered a judicial investigation.

Yet‚ the Court has come in for criticism of bias against the president and the political system. Proceedings against the president on charges of corruption that were pending in Switzerland were withdrawn under the amnesty law. The Court wants to know why, but is accused of unduly focusing only on the president while ignoring other beneficiaries of the law.

The test of the Court’s tolerance of the democratic political structure will come when it rules on the issue now before it: whether Parliament has an unfettered right to amend the Constitution. The Court may well follow the precedent of its Indian counterpart‚ which has repeatedly held that Parliament’s right to amend the Constitution is precisely that: a right to amend‚ not to abrogate. That Court has consistently limited the power of Parliament and kept it subject to judicial review. If the Supreme Court of Pakistan follows the same line of reasoning‚ there may be a clash between the two institutions. Lawyers, whose movement sapped a military regime of undiluted power‚ ushered in democracy, and an independent judiciary, have a stake in both institutions: Parliament and the Court.

Current wisdom suggests that an effective and mighty military operation backed by the will of an elected Parliament is sufficient to push back the insurgents. There is no doubt military offensives must be determined and resolute. The representatives of the people must also give legitimacy to the violence entailed in counterinsurgency efforts. But the issue goes beyond legitimizing use of force. Measures to counter the widespread present-day insurgency must succeed. There is no other option for Pakistan and the international community. Neither terrorists nor the brutal means they use can be allowed any space whatsoever. But the means that we‚ not they‚ use in this contest are critically important. The most effective weapon in any war is an empowered and emboldened local population that has enforceable rights within the system which is under assault. Denude that population of enforceable rights and you discard one of the most effective means of countering insurgency. Deny people an effective justice system and they become indifferent at best and inimical to the aims of counterinsurgency at worst.

Initially‚ the Taliban gave nothing to the population they controlled. They did not build roads‚ bridges‚ hospitals or schools. In fact‚ they destroyed these with impunity. They have blown up more than 300 schools and tens of bridges in the last five years. So why did people still turn to them in places like Swat‚ fleeing only when there was a military operation? The only tangible albeit tragic advantage that the Taliban had held was that they dispensed what some thought passed for justice—even if it was actually rough and brutal injustice—in “courts” convened in the open and under trees. Incredible though it is‚ this was the only charm that enabled the Taliban to win territory and subjugate populations in the first place. Deprive the people of the machinery for the enforcement of their rights‚ and you begin to lose the war. Now‚ in the wake of the unprecedented floods‚ extremists sympathetic to the Taliban are winning ground in ravaged parts of the country by providing relief and rations to the displaced and beleaguered.

Much of what is happening on Pakistani soil cannot be addressed with high-tech weapons alone. Nor can it be countered by cash‚ dole‚ or capitulation. More than a mere determined military response, the challenges of Pakistan require social reengineering. The mindset of violence has to be combated and changed. The issue is systemic and it can only be countered with systemic solutions like the reinforcement of civilian institutions and focused economic development in order to quell insurgencies. Today‚ Pakistan has a crying need for aid to restore its infrastructure and to ward off insurgents. In the long-run‚ it will need private investment‚ and plenty of it. An independent judiciary is critical for Pakistan’s long-term economic prospects. Few investors will tread where they fear their contracts will not be enforced.

As long as the West continues to attribute a mistaken identity to Pakistan‚ it will be unable to understand the land on which the insurgency is being waged. And it will be unable to understand a people who are its indispensable allies in the counterinsurgency. For decades‚ Pakistan has been perceived as a Middle Eastern sheikhdom. This started when eight-year-old Pakistan signed the Baghdad Pact in 1955 to join the Middle East Treaty Organization. The pact bonded Pakistan to a set of Arabic-speaking states in efforts to encircle the Soviet Union. It should have been realized even then that Pakistan was a square peg in a round hole. But the misperception lasts.

Pakistan is no doubt a Muslim state. But it is neither Arab nor Middle Eastern. Pakistan is a South Asian state. Unlike most Arab states which do not have an independent judiciary or any desire for it, being South Asian‚ Pakistan is wedded to the idea of an independent judiciary. Even though they may not be aware of the actual names‚ they resort in routine to such judicial remedies as habeas corpus. The Pakistani citizen aspires for due process. Pakistan can only continue to stand up to the insurgents in the months and years ahead if‚ along with massive rehabilitation efforts‚ we are able to strengthen the justice system not subvert it. Sense of justice inspires confidence‚ it gives people hope and spine.

Pakistan is no doubt a Muslim state. But it is neither Arab nor Middle Eastern. Pakistan is a South Asian state.

The people of Pakistan have generally had a dichotomous view of America over the past two years. U.S. policy professes to be hinged on the nurturing and sustenance of democracies around the world. No one disputes that. With institutions like the American Bar Association‚ the New York Bar‚ Harvard University‚ and the Mideast Institute celebrating the courage of the chief justice and lawyers‚ a positive image of the U.S. has been promoted. But on the other hand‚ the U.S. administration of President George W. Bush stood by silently as the people marched for their chief justice and for the rule of law. The chief justice and his children were locked inside their house for five months and not the faintest decibel of concern emanated from anyone in that administration. This was viewed by many here as an adversarial if not clearly hostile act.

No one wants to weaken the edifice of democracy or disrupt its progress. But no democratic structure is complete or even remotely sustainable without the existence of an independent justice system peopled by fearless judges‚ who ask questions and challenge wrongs. That is axiomatic. It is in a democratically-elected government’s own interest to consolidate an independent judiciary and empower it.

Bare ballot democracy must be distinguished from full constitutional democracy. Constant vigil by the courts to keep everyone within the bounds of the law is an irreducible part of the latter. Democracy does not mean the mere casting of the ballot once every five years with no enforceable rights in the intervening periods. Democracy means the complete system of periodic franchise along with enforceable rights‚ guaranteed at all times by clean parliamentary and judicial processes. It is only with such a combination that Pakistan can be saved from a ravaging and cancerous militancy. Only this combination can create and protect institutions‚ serve democracy‚ and help Pakistan and the world defeat terrorism.

Ahsan‚ one of the leaders of the lawyers’ movement‚ is a former federal minister for law and interior. He is also the author of The Indus Saga: From Pataliputra to Partition. From our Sept. 13 & 20, 2010‚ issue.