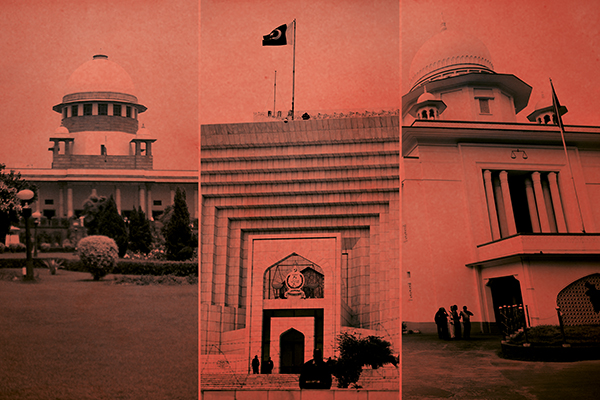

From left: No credit, Aamir Qureshi—AFP, Munir uz Zaman—AFP

Pakistan’s former chief justice hopes his legacy will live on. Nothing could be worse for the country’s justice system.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]ftikhar Chaudhry wasn’t reinstated as Pakistan’s chief justice because of the law. His return to the bench, both in 2007 and 2009, owed to the street agitation that had been organized by opposition parties and violence-addled lawyers, whose sharply divisive rhetoric Chaudhry embraced and surpassed in his own judgments, each more passionate than the last. The nonintellectual Chaudhry does not rank among Pakistan’s greatest jurists; but he was likely the most controversial man to ever lead the Supreme Court.

During the last four years, the grandstanding Chaudhry effected and exploited political polarization in the country to burnish his populist credentials. He finally retired on Dec. 11—an event he had hoped to delay for some years by having “well-meaning” lawyers file at least two petitions claiming Chaudhry’s indispensability. However, the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz), which came to power in May and had supported Chaudhry’s triumphal reinstatement in 2009, did not want the mercurial judge in its hair.

Chaudhry was judge, jury, and executioner. Wont to issuing Islamic and anticorruption bromides and playing to the press gallery, he was a wrecking ball who meticulously demolished his perceived enemies—in spite of the law. Chaudhry was one of the judges who had validated and legitimized the 1999 coup against Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. He swore an oath of personal allegiance to the coup-maker, Gen. Pervez Musharraf, in 2000. Five years later, he was rewarded with the top judgeship.

His initial “activism,” reproved by lawyers, had been welcomed by laymen. The historically meek Supreme Court was showing flashes, finally, of some independence—or so it was thought at the time. The Chaudhry court’s activism was not unprecedented for South Asia. In fact, his judicial overdrive emulated the India and Bangladesh models. The activist Supreme Courts there also clashed with the executive and legislative branches—but not because they sought primacy over other branches of government; rather, they set out to compensate for the poor-quality of governance that characterizes most Third World states. This, too, had been Chaudhry’s stated goal during the last tumultuous years of his rule.

Emulating the ‘Enemy’

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n India and Bangladesh, the increasingly populist apex courts curtailed due process by removing the trial stage afforded to defendants in normal prosecution. This is precisely what Chaudhry did by firing up his court’s suo moto powers to take up with finality “human rights” cases even in the absence of a complainant. The Indian and Bangladeshi courts also challenged and cast aside legislations. Likewise Chaudhry, who rejected the unanimously-passed 18th Amendment to the Constitution and demanded that he, as chief justice, be given power to appoint judges without any parliamentary oversight or involvement. For reasons that remain indefensible, Parliament buckled and accommodated his desires through another amendment.

The aggressive overdrive of the Pakistani, Indian, and Bangladeshi Supreme Courts was a reaction to their long suppression by their respective executives. Browbeaten by uniformed and non-uniformed rulers in Islamabad for decades, Pakistan’s Supreme Court began to be influenced by its Indian counterpart most visibly in 1997, when it defied the executive by taking on then-prime minister Sharif, whose party members—including present-day federal ministers—stormed the court. In the end, Sharif triumphed; and the-then chief justice resigned. The Supreme Court swung back into docility.

In India, the judiciary-executive clash came early on. “No Supreme Court and no judiciary can stand in judgment over the sovereign will of Parliament representing the will of the entire community,” India’s first premier Jawaharlal Nehru told the Constituent Assembly. “If we go wrong here and there, it can point out, but in the ultimate analysis, where the future of the community is concerned, no judiciary can come in the way.” The Indian chief justice, M. Patanjali Sastri, shot back: “Our Constitution contains express provisions for judicial review of legislation as to its conformity with the Constitution.”

The Indian Supreme Court embarked on a 20-year activist streak after the assassination of Indira Gandhi, a prime minister whose attitude toward the court had been dismissive at best. Gandhi was Nehru’s daughter and had insulted the judges during her 1975 state of emergency. Activist Chief Justice Prafullachandra Natwarlal Bhagwati, who retired in 1986, solicited cases of human-rights violations from the public, but he was candid enough to call this “judge-led” and “judge-induced” litigation. The courts saw a proliferation of fresh public-interest litigation while some 30 million pending cases went unattended. The Indian courts became so interventionist that they even started managing college admissions and hospital routines. This lapse into micromanagement was finally brought to a halt by the Delhi High Court, which ruled that “no judge shall take suo moto notice of any news item without [its] prior permission.”

The hyperactivism of the Indian courts was criticized by successive governments. “What is required is a conscious realization of unseen boundaries that cannot be traversed without causing embarrassment and even injustice to the democratic system and the rights of its citizens,” complained Indian President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam in 2005. “All organs, including the judiciary, must ensure that the dividing lines between them are not breached,” said Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2007.

Indian judicial activism was also criticized by some lawyers. Indian chief ministers and high-court chief justices held a summit, attended by Prime Minister Singh and Chief Justice K. G. Balakrishnan, on Aug. 16, 2009, in which the people’s elected representatives criticized the unelected arbiters. “Everyone was surprised when some chief ministers raised the issue of judicial overreach,” wrote Indian lawyer A. G. Noorani. “At least two of them expressed concern over the manner in which courts summoned senior government officers to appear in court in minor issues.” This gave the judges pause. In 2010, following the lead of Supreme Court Chief Justice S. H. Kapadia, Justice Markandey Katju, too, issued a rebuke to judges whose activism had run riot. The Supreme Court would no longer weigh in on “matters of policy,” said Katju. “Supreme Court judges should do their job and not become a Parliament and make laws.”

The Pakistani judiciary “borrowed” from its Indian counterpart the trend of expanding suo moto public-interest litigation. The Indian Supreme Court as well as the high-courts hauled up the bureaucracy on the basis of newspaper reports and distress calls issued by citizens. India experienced an expected backlash to this kind of activism, which resulted in judges themselves splitting on the issue. In Pakistan, Chief Justice Chaudhry set some kind of record by issuing hundreds of suo moto notices.

In Bangladesh, the political environment that enables judicial activism is markedly different, suffering as it does from extreme polarization wrought by the two main parties, Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party. The Dhaka court went activist after the Awami League’s 2008 election win. It secularized the Constitution, banned politico-religious parties, and reignited controversy over the normative nature of the state. But the court’s work is rendered uncertain because of the inexhaustible vendetta between the two parties. By doling out riot-inducing death sentences through special tribunals to religious leaders for participating in the 1971 civil war, the Dhaka government has blunted the legitimacy of the court’s activism.

Chaudhry meticulously demolished his perceived enemies—in spite of the law.

But what some see as activism by Bangladeshi courts may actually be subservience. The fundamental principle of separation of the judiciary from the executive is still to be respected by Dhaka. Until 2009, subordinate courts remained formally subject to executive control with magistrates performing the dual role of executive officer of the government and judicial officer. Allegations continue to fly in Dhaka about the conduct of high-court judges who “refuse to hear matters on the grounds of feeling embarrassment.” In May 2012, some judges felt “embarrassed” to hear the bail petitions of prominent opposition leaders, while yet another bench passed dissenting orders on one of these bail petitions.

The South Asian judiciary became activist for some common reasons as well as some uncommon ones. India seems to be settling down to a middle course of judicial conduct while Pakistan and Bangladesh will go through self-correction, away from accusations of partisanship and some other extreme tendencies, only after “normalization” of the political landscape.

In India, judicial activism did not unfold in a landscape of violence. Even then, strong voices were raised from within the Indian superior judiciary against the “activist” tendency of some judges to fly off the handle. In Pakistan, violence characterized the movement launched by lawyers to get the government to reinstate judges fired by Musharraf. Pakistani lawyers in 2007 had threatened the Supreme Court with arson to get it to ignore government pressure and issue a verdict of their liking, i.e., ordering the reinstatement of Chaudhry, who had been fired that March. (He would be fired again in November.) In a society where power is seen as the legitimizing principle, a judiciary grown “powerful” became conflated with the constitutional norm of an “independent” judiciary. This condition, specific to Pakistan in the reassertion of the judiciary, affected the post-restoration Supreme Court, setting it firmly apart from India’s.

Post-March 2009, after Chaudhry was reinstated to the Supreme Court for the second time, the pendulum of public opinion swung violently in favor of the previously-subjugated Supreme Court. The court leaned even more on public-interest litigation, liberally used suo moto jurisdiction to hound a clearly incompetent executive, and its actions were seen as “excessive” by its critics. The empowerment of the court was in measure with the disempowerment of the other two institutions, the executive and legislature, through political discord. Complications that arose in Pakistan in the aftermath of the 18th Amendment were compounded by the vast public support the court was able to rely on. Civil-society activists, determined to roll back the autocratic era of Musharraf, joined the aggressive phalanx of lawyers to give the court the backbone it needed to further expand its intrusive questioning of executive actions. The court expressed itself less as an “independent” institution—which is allowed by the Constitution—and more as a powerful body owing its clout to the politicization of the judicial process.

The Chaudhry court also followed the lead of its Indian counterpart in discovering a “basic structure” to the Constitution which, it held, even Parliament cannot tamper with while passing amendments. In India, most jurists accept the basic-structure theory in the context of the Supreme Court’s confrontation with Prime Minister Gandhi, who tried to undo the judicial findings about her invalidated elections through lawmaking in Parliament. The Indian court referred to the purity of the Constitution’s “basic structure” to foil her attempts at validating her election through the legislature.

In the case of Pakistan, Chaudhry’s in-passing remarks while hearing an appeal against a provision in the 18th Amendment aimed at introducing the role of the legislative into the mechanism of induction of judges signaled that the court would rely on the text of the 1949 Objectives Resolution as the “basic structure” of the Constitution to strike down the amendment. Supreme Court lawyer Salman Akram Raja took issue with this trend of relying on the Objectives Resolution to set up a principle of “intervention” in the function of the legislature beyond the accepted norm of “judicial review” on the ground that in the past the court had declared that “no part of the Constitution or any other statute could be struck down by the High Courts or the Supreme Court on the basis of inconsonance with the injunctions of Islam.”

Disturbed by the negative effect public-interest litigation had on the backlog of normal cases before the courts, Supreme Court lawyer Ashtar Ausaf Ali, like many other lawyers devoted to the “independence” of the judiciary, had this to say: “As far back as 1958, the Supreme Court of Pakistan declared that the high-courts do not have suo moto powers under the-then 1956 Constitution. In 1971, the Supreme Court made a similar declaration in respect of the 1962 Constitution. The provisions vis-à-vis powers of high-courts in the present Constitution of Pakistan more or less resemble those in the 1962 Constitution.” It appears that the terminal effect of the suo moto resort of the judiciary has been the same in India and Pakistan.

Bitter Harvest

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]fter the February 2008 elections, the two mainstream parties—Pakistan Peoples Party and Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz)—Musharraf had marginalized from the political process achieved success and committed to act together in the matter of the judiciary’s restoration. The PPP promptly ordered the release from house arrest of all judges, but took its time in restoring Chaudhry. This had two important consequences: it caused a rift between the two parties, and it birthed a perceived rivalry between Chaudhry and the PPP-led government. What followed Chaudhry’s restoration—achieved in 2009 at the behest of Pakistan’s Army chief, Gen. Ashfaq Kayani—was an unfolding of a war between the judiciary and the executive that dimmed the hope civil society had of establishing an order free of old biases.

In 2006, the Chaudhry court displayed its lack of knowledge or opposition to the free-market economic order prevailing in Pakistan when it quashed the privatization of Pakistan Steel Mills. His court never seemed to have registered the harm it did to the process of privatizing loss-making state-owned industries through the steel mills judgment. In 2013, the mills are making a loss of about Rs. 2 billion a month and no foreign buyer is interested in taking them off the government’s hands. Following his 2009 reinstatement, Chaudhry’s court further compounded its economic activism by indulging in price fixing in an economy governed by demand and supply, despite decades of pitiful examples of market intervention gone wrong. The damage done by his “activism” in the crucial energy sector may turn out to be more lasting than most observers calculate. The tendency of Chaudhry’s court to resort to aggressive speechifying also attracted the comment that judges should speak only through their judgments; Chaudhry, while asserting the primacy of national law over international law in one case, actually referred, inappropriately, to Pakistan’s “nuclear power.”

The most irreversible damage that can be done to any court process is its politicization. The best judgment is rendered useless if delivered in an environment polarized by politics. This is what is happening in Bangladesh and has been happening in Pakistan. During the Chaudhry years, the PPP said it was being hounded by the court while the opposition PMLN was being let off the hook if not being brazenly favored. Some of the cases against the PPP recoiled badly on the Chaudhry court and brought the judicial process into disrepute.

“During the term of this chief justice, Pakistan saw a massive expansion of judicial overreach, hyper-judicial activism and, frankly, a quasi-judicial dictatorship,” Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, the 25-year-old PPP patron-in-chief, wrote for Huffington Post following Chaudhry’s retirement. As “Chaudhry retires, he leaves the court with a sullied reputation once again … The [chief justice] often used the constitutional provision that makes it illegal for anyone to ‘ridicule’ the judiciary as justification [to suppress free speech]. The irony being that it was not the courts’ critics but the chief justice himself who brought the court into disrepute.” Further, he writes: “I am hopeful with the retirement of the infamous chief justice, Pakistan will not only have an independent judiciary but an unbiased one as well. Unlike Iftikhar Chaudhry, the remaining justices are the true heroes of the lawyers’ movement.”

Aamir Qureshi—AFP

Laggard Son

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]orruption charges hit close to home last year after businessman Malik Riaz Hussain went public with accusations that he was being “screwed” and blackmailed by Arsalan Iftikhar Chaudhry, the self-righteous chief justice’s son. The son’s financial scandals broke after he kicked up his heels holidaying abroad with hundreds of millions of rupees gouged from real-estate baron Hussain. (There remain rumors of other businessmen being similarly exploited, but so far only Hussain has dared to step forward.) Earlier, the police department, according to a retired officer, had been forced by Chaudhry to induct the laggard son as an officer—even though he had not passed the required competitive civil service examination. The judge was furious, but less so with his son and more with the public rancor over the son’s audacious misdeeds.

Chaudhry took up the case himself by exercising suo moto notice of rumors that a foreign newspaper was planning a major exposé. He dismissed conflict-of-interest concerns by comparing himself to Islamic caliphs. In fact, during one of the hearings over his son’s matter, Chaudhry arrived in court brandishing a Quran and a rosary. Cases against the accuser, Hussain, were opened, and the judge threatened his economic ruin. Eventually, under public pressure, Chaudhry removed himself from the bench, and the one-man tribunal ordered by the court to investigate the allegations came up with a damning report that said both Hussain and Arsalan Iftikhar Chaudhry appeared to have wealth beyond their declared incomes. The court swept up the case by judging this a dispute between two private individuals. This did precious little for Chaudhry’s tarnished reputation.

Chaudhry was beloved by the Taliban and had an army of lawyers who could rough up anyone.

The International Commission of Jurists’ unflattering report on Pakistan’s judiciary, Authority without Accountability: the Search for Justice in Pakistan, released on Dec. 5, says the Arsalan case proved right the “well-founded criticisms of inconsistency in [the Chaudhry court’s] approach to human rights.” It notes that the court had originally ordered the National Accountability Bureau to look into the matter, but accepted Arsalan Iftikhar Chaudhry’s allegation that the anticorruption body was “biased” against him and so constituted the one-man inquiry commission.

“It is unclear why or on what basis the Supreme Court agreed to review its earlier order when it had already decided the matter was not of public importance and thus not within the purview of its jurisdiction under [the Constitution’s] Article 184(3). It is equally unclear why the court ordered the appointment of a commission in a matter that could have been handled through the National Accountability Bureau or the regular police force,” states the report. “The Supreme Court apparently changed its position again on the question of ‘public importance’ after the [Shoaib] Suddle commission’s interim report of Dec. 6, 2012, found that Arsalan Iftikhar had admitted before the commission that he had availed himself of two of the three foreign visits alleged by [Hussain],” it continues. On Dec. 7, the court dissolved the Suddle commission. “Thus, over the course of six months, the Supreme Court appeared to change its views at least three times with no clear justification on the issue of whether allegations of corruption against the chief justice’s son—and initially the chief justice himself—were of ‘public importance.’”

On the other hand, Chaudhry doggedly pursued families of politicians—including that of Yousaf Raza Gilani, who was dismissed as prime minister by the court, and that of former Punjab chief minister Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi.

“It is common knowledge that Arsalan Iftikhar Chaudhry has plundered billions of rupees,” says Abid Saqi, president of the Lahore High Court Bar Association, who has filed references against former judge Chaudhry. “He was the most hopeless chief justice in the history of this country, a lethal combination of arrogance and ignorance.” And it doesn’t end with the Arsalan case, if Rawalpindi-based Shahid Orakzai is to be believed. He’s filed a complaint with the Supreme Judicial Council against Chaudhry, alleging that the former chief justice gave undue relief through his court to a real-estate businessman, whose son recently wed Chaudhry’s daughter.

Iron Grip

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the past, the executive was so powerful and autocratic that it ignored court verdicts, so much so that courts took to postponing decisions they thought would offend the executive. But the PPP-led coalition government was weak, out of favor with the Army, at loggerheads with the PMLN, fearful of jihadist militias, and looked upon by the rightwing media as an American stooge. Chaudhry, on the other hand, was beloved by the Taliban and had an army of junior lawyers who could rough up anyone at will, including policemen and journalists, with impunity. Chaudhry’s first-among-equals status also suppressed dissent in his court, even in blatantly controversial decisions. In 2011, the International Commission of Jurists reported: “We heard insinuations that the chief justice picked colleagues who would determine cases or reach decisions in the way he would have himself decided the case. There were also suggestions that judges who were considered partial to his views in a given case would be given preference for selection in hearing a matter.”

Only a court led by Chaudhry could get away with the sacking of a sitting prime minister. After it ousted Prime Minister Gilani last year, retired Indian judge Katju wrote the following in a column for The Hindu: “How can the court remove a prime minister? This is unheard of in a democracy. The prime minister holds office as long he has the confidence of Parliament, not the confidence of the Supreme Court. I regret to say that the Pakistani Supreme Court, particularly its chief justice, has been showing utter lack of restraint. This is not expected of superior courts. In fact, the court and its chief justice have been playing to the galleries for long. It has clearly gone overboard and flouted all canons of constitutional jurisprudence.”

The Gilani ouster exposed the Chaudhry court to accusations of political partisanship. Aitzaz Ahsan, architect of the lawyers’ movement, had warned Chaudhry against breaching dividing lines. In a 2010 piece for Newsweek, Ahsan wrote: “The [Indian] court has consistently limited the power of Parliament and kept it subject to judicial review. If the Supreme Court of Pakistan follows the same line of reasoning, there may be a clash between the two institutions. Lawyers, whose movement sapped a military regime of undiluted power and ushered in democracy and an independent judiciary, have a stake in both institutions: Parliament and the court.”

The International Commission of Jurists, in 2011, also took a dim view of the Chaudhry court’s refusal to accept the powers of Parliament. Its report that year criticized the court’s position on the appointment of judges, and the application of its suo moto powers and interplay with the media. Chaudhry got Parliament to pass the 19th Amendment to win his office power over the induction of judges. This negated the principle of nulls index in cause sue, i.e., no one should be a judge in their own cause, said the Commission. The Chaudhry court not only adjudicated the issue over future inductions but also “concluded that in a conflict between Parliament and the judiciary, the latter ought to have a stronger position.” The Commission held as “disingenuous” the court’s claim that the involvement of political institutions in the appointment of judges was incompatible with the rule of law and respect for “human rights.”

Weeks ahead of Chaudhry’s retirement, Pakistan’s Parliament passed a unanimous resolution objecting to the court’s tendency to set aside the deliberated opinion of the legislature. Critics are agreed that the court’s suo moto addiction has curtailed the “due process” integral to any system of justice: if the Supreme Court hands down an apparently unfair verdict, there is no appeal against it except for a review. Also, the Chaudhry court’s focus on high-visibility “public interest” cases—tragically, some pertaining to the economy—diverted its attention from the lower judiciary, where judges helplessly interface with terrorism, abstain from convicting terrorists, and wink at the “replacement” of big under-trial terrorist prisoners with hired surrogates.

What happens now, post-Chaudhry? According to Chaudhry’s speech to the Sindh High Court Bar Association in Hyderabad on Dec. 8, don’t expect anything different. “There will be no difference when I leave,” he said. “All the judges sitting there [at the Supreme Court] are heroes and they have been giving good judgments.” By Chaudhry’s reckoning, the day of the nonintellectual and passionate judge is not yet done. He expects his legacy of revenge cloaked as justice to endure. For the sake of the Pakistani judiciary’s independence, one can only hope that he is proven wrong.

With Benazir Shah. From our Jan. 11, 2014, issue.

3 comments

Bravo!

One hopes and prays that the new Chief Justice does believe in non partisan due process and dispassionate rule of law indifferent to outcome.

A further weak hope is that senior judiciary will persuade government to reform trial courts. This country is crying for universal, affordable, uncomplicated and speedy resolution of conflicts, we are desperate for rule of law for a semblance of justice. Without it we will have no peace and no progress.

Wonderfully written article; a pleasure to read

What happens now, post-Chaudhry? Don’t expect anything different. Well that is optimistic. Jillani is prove to be a better adjudicator.