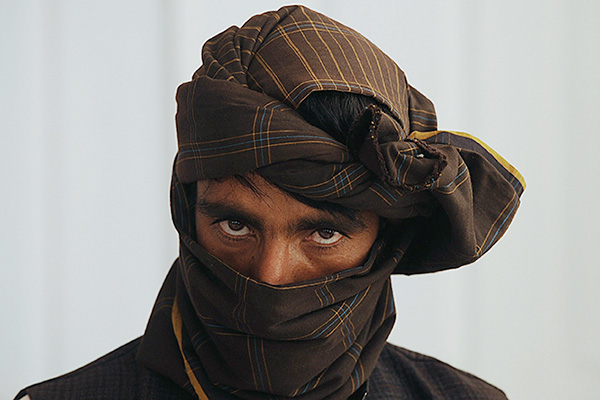

Afghan Taliban scramble for upper hand in peace talks as deadline for U.S. exit approaches.

The United States, the Afghan government, and Taliban insurgents are all scrambling for advantage as the clock ticks down in the search for an unlikely peace deal before foreign military intervention ends in Afghanistan.

U.S. troop numbers will halve to 34,000 within eight months. The British operate just 13 bases in the hotbed province of Helmand, down from a peak of 137. Other NATO allies have already withdrawn.

But the December 2014 deadline to leave increasingly looks like a hostage to fortune as the Taliban ramp up attacks in Kabul and pose as the government-in-exile at their new office in Qatar.

“The Americans need this negotiation, not the Taliban,” said Waheed Mujda, an analyst who worked as a foreign ministry official in the 1996-2001 Taliban government. “Without a peaceful settlement, the situation will worsen. The Taliban will intensify attacks, more rural areas will fall under their control, and the highways and main roads will become insecure. They think that this way they will have the upper hand in any peace talks. As they often say ‘the Americans have the watch, but we have the time.’”

U.S. President Barack Obama was accused earlier in his presidency of being slow to seek a political solution to end the 12-year conflict, but concerns are rising that a deal must now be bought at any cost.

When the Taliban opened their office in Qatar last week, raising their flag and using the name of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, a furious President Hamid Karzai broke off security talks with the Americans and threatened to boycott any peace process altogether.

Bruce Riedel, director of the Brookings Intelligence Project, says that the U.S. failure to orchestrate a smooth opening of the office reinforced suspicions about Obama’s bottom-line. “The perception in the region is that Washington is so desperate for a political process that it’s willing to sacrifice the interests of its Afghan partner,” he said. “That’s a very dangerous perception now sitting out there. It’s got to become a process in which Afghans talk to Afghans. And Karzai has said he’s not going to talk. He wants negotiations with a Taliban that reinvents itself as a political party.”

Pakistani author Ahmed Rashid, who has written extensively about Afghanistan and the Taliban, said Karzai’s intransigence partly reflected wider Afghan anger but accused him of being part of the problem. “He has always envisaged a kind of Taliban surrender to him or a Pashtun meeting of tribes in which the Taliban would acknowledge Mr. Karzai as their leader and tie the traditional turban around his head,” Rashid wrote this week in The Financial Times. “Clearly, none of this is going to happen. Why would the Taliban surrender when they had beaten the U.S. military to a standstill or bow before the Afghan they most despise? Yet Mr. Karzai refused to accept anything less.”

Only hours after the Qatar office opened, a Taliban rocket attack killed four Americans on the largest military base in Afghanistan. Just days later, a suicide squad targeted the presidential palace and a CIA office, in the most audacious assault in Kabul in years.

“The insurgents’ primary mode of political expression in the near future will remain fighting, not party politics,” said a paper released on Wednesday by the International Crisis Group think tank.

Amrullah Aman, a former Afghan general turned popular TV pundit, said that as 2014 gets closer, the Taliban are convinced that “their success is directly proportional to American withdrawal.” He said: “Their political office in Qatar has emboldened them to do more operations to put pressure on the government to give in to their demands.”

But others do not believe the Taliban hold all the aces, despite the fast-approaching U.S. exit and a weak Afghan government that faces a tricky presidential election in April.

“The Taliban overestimate their own capabilities and underestimate the Afghan government’s security forces,” said Kate Clark, senior analyst at the Kabul-based Afghanistan Analysts Network. “They remember 1996, and how they took most of the country without much fighting. I don’t think it is going to be like that again. They underestimate how difficult it would be, whether or not the Americans are here after 2014.”

The Taliban themselves have remained largely silent since the unveiling of their Qatar office, except to claim responsibility for the presidential palace and U.S. base attacks.

In Qatar, they read out a statement demanding an end to the “occupation,” meaning no U.S. troops could stay, despite Afghan-U.S. talks designed to reach a deal on a residual force post 2014. The rebels’ five-point agenda also said the office may be used to meet unspecified Afghans “in due appropriate time”—a hint perhaps that their refusal to talk with representatives of Karzai’s government could be negotiable, if not immediately.

“The Taliban are waiting,” according to a mid-level Taliban member in northwest Pakistan who declined to be named. “We should not expect an immediate solution from these talks, it will take time.”