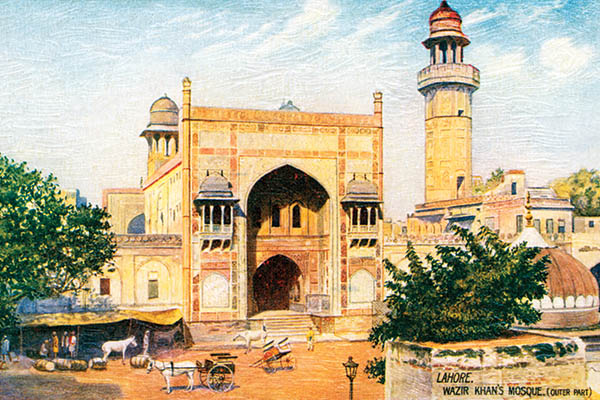

Wazir Khan’s Mosque (Outer Part). Lahore Series I. No. 8965. Raphael Tuck & Sons, London, c. 1905. Embossed colored halftone, Divided back. Courtesy Omar Khan

Revisiting, through postcards, Pre-Partition Lahore

Postcards were the Instagram of their time. Between 1895 and 1900 the world moved from exchanging millions of postcards per year to billions—with the vast majority being printed in Germany. Postcards quickly became the world’s preferred mass exchange of visual information, the first time people got to see far-off places, often in color, on a global scale, delivered to their mailboxes, with a personal message from a loved one. Postcards, in many ways, began the ‘picture-mad’ age we live in today.

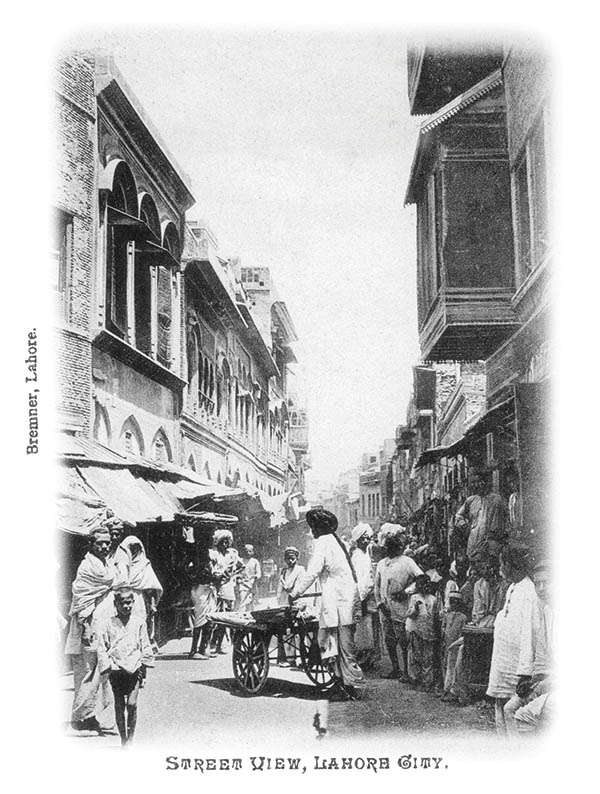

What is now Pakistan, and particularly Lahore, very much participated in this visual revolution. Although the first postcards of the British Raj were produced in Kolkata and Mumbai around 1897, and there are some postcards of Lahore likely from the late 1890s, the first major local producer of Lahore postcards was the photographer Fred Bremner. His black and white postcards like Street View, Lahore City, based on albumen photographs, date back to at least 1903 and are full of the rich detail of the collotype printing process. Like most cards from the subcontinent, they were printed in Germany—the publisher would send a photograph to a printing house, who would return a set of postcards by ship and train; the customer might purchase it from Bremner’s studio near the Mall, then mail it to someone in England. A single postcard might criss-cross the world many times before reaching its destination, they were truly international products. Note the white space at the bottom of the image for the written message; only addresses and stamps were allowed on the back of postcards at this time. With studios at different points in Karachi, Quetta and Simla, Bremner published dozens of postcards of Lahori landmarks for two decades.

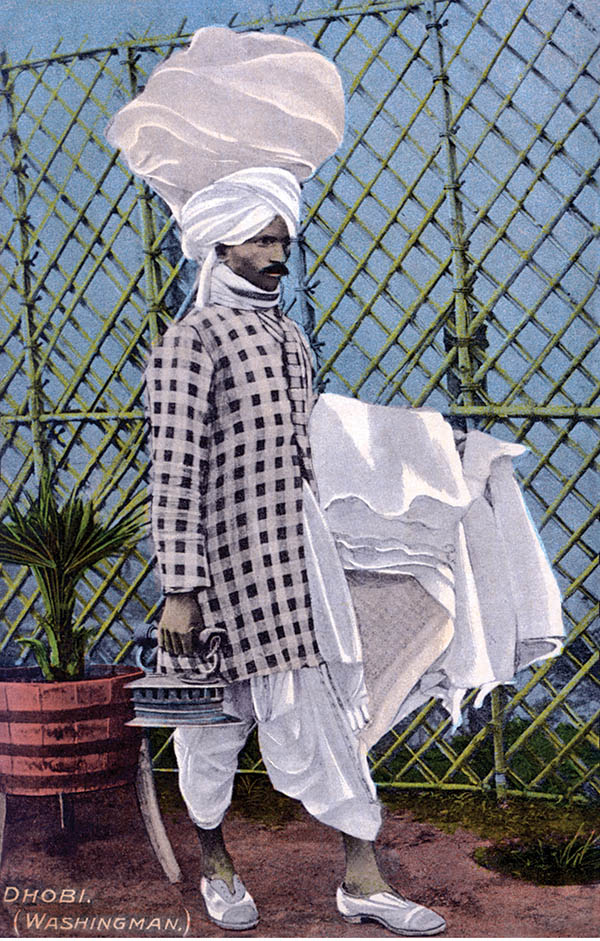

Dhobi. (Washingman.). Moorli Dhur & Sons, Ambala, c. 1908. Colored halftone, Divided back. Courtesy Omar Khan

Other local photographers—Bliss & Tilden, Shanker Dass, D.M. Bali—flourished after 1905, but towards the end of the decade it was Raphael Tuck & Co., based in London, that became one of the preeminent producers of postcards featuring Lahore—a reign that spanned into the 1930s. Their Oilette series offered two sets of six postcards dedicated to Lahore and showed landmarks like the Badshahi and Golden Mosques, the Punjab Club, the Lahore Museum and Post Office, and the Shalimar Gardens. One of my favorites is Lahore. Wazir Khan’s Mosque (Outer Part). Tuck’s cards were usually printed in Britain, using the halftone process with tiny dots invisible to the naked eye used to render an image from color inks (this is still the process used by newspapers, magazines, books and dot-matrix printers today). Being cheaper for mass production, halftones became common for postcards around 1910. Oilettes were supposed to be made from oil paintings, but most actually started as photographs, which were then richly colorized. Wazir Khan’s Mosque is also a special embossed card; if one looks carefully at the sky and mosque front, one sees the lines pressed into the card which give it a three-dimensional feel even more like that of an actual oil painting (the postcard business was always innovating for competitive advantage). It is a glorious postcard, highlighting the beauty of the mosque rising above its famous courtyard entrance, where everyone from the great Mughals to Rudyard Kipling once walked. Well-enhanced shadows give it depth. Like most Oilettes, it has a descriptive caption on the back, where messages were permitted after 1905, so that the image could take up the complete front of a postcard.

The Huzuri Bagh, Lahore. K.C.Mehra & Sons, Peshawar, c. 1908. Colored halftone, Divided back. Courtesy Omar Khan

Another major Lahore postcard publisher was K.C. Mehra and Sons, originally a bookseller based in Peshawar. They too had a splendid series of colored halftone cards of city landmarks, printed by Stengel & Co. in Dresden, Germany, perhaps the world’s largest postcard printer at the time. The Mehra series includes The Huzuri Bagh, Lahore. It shows the second terrace, now dismantled and in storage, on the delicate marble pavilion built by Ranjit Singh in 1818. Here is where the Maharajah liked to hold court, even underground during the hot summer months. Today a similar view, with the Lahore Fort gates, looking out from the steps of Badshahi Masjid and Allama Iqbal’s grave in the foreground, is an iconic national view.

Street View, Lahore City. Bremner, Lahore (No. 118), c. 1903. Collotype, Undivided back. Courtesy Omar Khan

Another major publisher of Lahore postcards, perhaps the largest after about 1910, was Moorli Dhur & Sons in Ambala, a large railway junction town. The firm published a wide series of postcards of Punjab and the northern subcontinent, and seems to have hit economies of scale in printing and distribution that led it to dominate smaller regional publishers. Among their outstanding cards is the colored halftone Dhobi. The geometric cane pattern, the sparkling white clothes and iron in the dhobi’s hands combine to create a beautiful effect. Wouldn’t you want to hire him?

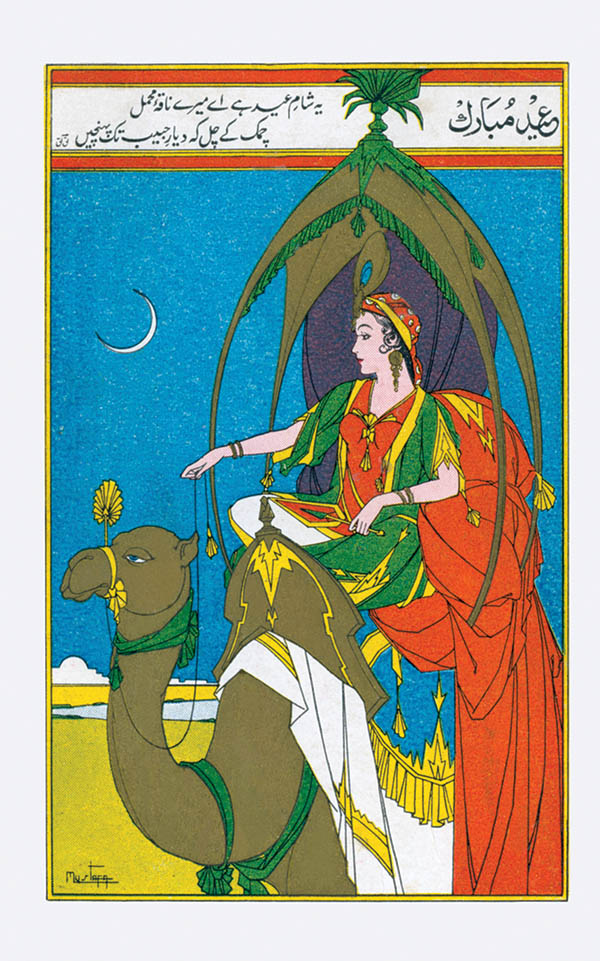

Postcards allow us to see what people a hundred or more years ago considered important, how they represented themselves to each other and to people around the world. As an early form of mass communication, they are a priceless window into history. Of course some displayed colonialist prejudices, but in general they were soon adopted by local publishers, photographers and producers and used for their own purposes to display the richness of the world and people around them. Lahore became particularly known for splendid Eid postcards, like the lithographic Eid Mubarak card signed by the artist Mushtaq, published by H. Ghulam Mohd & Sons around 1940 (note that it is a woman on the camel). Later in the decade, postcards also played an important role in the anti-colonial struggle and the Pakistan Movement.

Eid Mubarak. Mushtaq. H. Ghulam Mohd. & Sons, Lahore, c. 1940 (postmarked 1942). Lithograph, Divided back. Courtesy Omar Khan

By then other media forms, like radio, movies and the telephone offered means of communication that made the postcard less important as a medium than it was at the turn of the century. Nonetheless, the concept of a postcard—an image with a personal message—remains very much alive on the digital platforms people use around the world today. Today, we call them ‘posts,’ but they retain that old sense of a personal greeting from someone, somewhere, who wants to share something meaningful with you.

Khan is the author of Paper Jewels: Postcards from the Raj (Mapin/Alkazi, 2018) and From Kashmir to Kabul: The Photographs of John Burke and William Baker 1860-1900 (Prestel/Mapin, 2002). You can find more postcards found by him at www.PaperJewels.org

From our March 9 – 23, 2019 issue